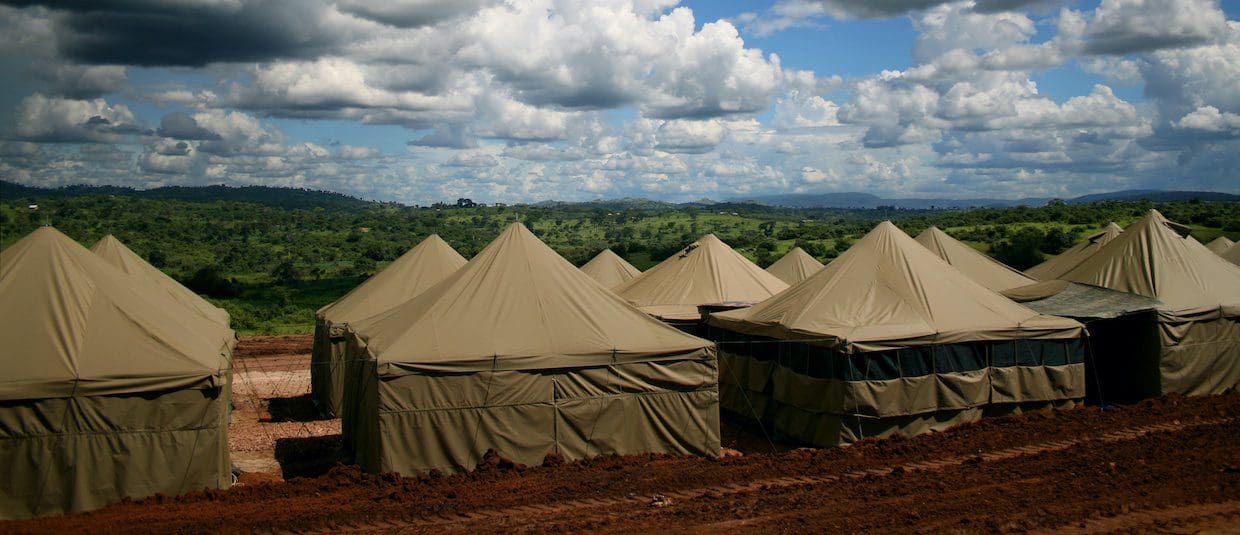

Post photo: Military camp in Africa | Bihanga | © EUTM Somalia

This article first appeared in French Journal Financier de Luxembourg (13.9.2023)

On August 30, 1954, the French National Assembly put an end to the plans for a European Defense Community and a European Political Community. The absurd idea of creating a European army before defining a European security policy was abandoned. The Washington Treaty of 1949 was amended to create the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and to give it, in law, by the new Article IV of the Treaty, and in fact, the monopoly of the means of military action in Europe. The[1]Efforts made since then by European leaders of all stripes to get out of this dependence were almost in vain: the Europeans were unable to stay in Afghanistan after the departure of the Americans.

Following the rejection by the Benelux and Italy of the confederal Europe proposed by de Gaulle (the Fouchet plans) until minds were ripe for federalism, it was not until 1986 and the Single European Act that we considered developing a European defense. The latter should have been both the military element of European integration and the European pillar of the Atlantic Alliance. [2]In 1992, the Maastricht Treaty structured the EU into three pillars: Community Affairs; Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP); Justice and Interior. The CFSP should have led to a common defense. [3]This proved impossible because President Mitterrand rejected political union. “It would have closed our internal tears, would have brought us the sharing of a common destiny, a destiny that implies common responsibilities of defense and security.” Chancellor[4]Kohl explained to him in vain that federalism is the only relevant form of supranational political integration.

Without having established a state and therefore a political-military command unit capable of developing sufficient military capabilities, Europe was unable to restore peace in Yugoslavia in the early 1990s. This displeased the Americans, who did not want to intervene in the Balkans, secondary to them. Nevertheless, in 1994, under a United Nations (UN) mandate, NATO intervened militarily for the first time, thanks to US forces. Unfortunately, the resulting Dayton Peace Accords of 1995 did not make Bosnia easily governable.[5]

In 1999, on 1 May, the entry into force of the Treaty of Amsterdam of 22 July 1997 enabled the Cologne European Council of 3 and 4 June to found the European Security and Defense Policy (ESDP). In October, Mr Solana became, until the end of 2009, Secretary-General of the Council of the EU and High Representative for the CFSP. The Helsinki European Council in December set up the Political and Security Committee (CoPS) and the Military Committee (EUMC), composed of the Chiefs of Defense of the Member States, and defined the 2003 Headline goal, i.e. an autonomous defense capability of 50,000 to 60,000 men, available within 60 days and for at least one year.

In June, the European Council took over command of the Kosovo Force from NATO. On 21st November Defense Ministers presented a plan, never carried out, to deploy in 2003 a force of 100,000 men, 400 combat aircraft and 100 ships, capable of maintaining a mission of 60,000 men for one year. In December, the European Council transformed the[6] Headline goal into a “catalogue of forces” and added to the EU an Institute for Security Studies, a satellite center and a strategic staff, such as NATO's military staff.[7][8]

At the end of 2001, the Laeken European Council set up informal meetings of European defense ministers and declared ESDP operational, as if the EU were capable of conducting crisis management operations, whereas it does not have an operational headquarters, which is what SHAPE is for NATO. This is why the EU and NATO conclude a “Strategic Partnership Agreement” supplemented on 11 March 2003 by the “Berlin More” Agreement, which extends EU access to NATO planning capabilities and assets. The exchange of classified information is regulated.

In 2003, the Treaty of Nice entered into force; it renews the architecture of the EU institutions, makes decision-making more flexible and states in Article 17 that: 'The CFSP shall include all matters relating to the security of the Union, including the progressive framing of a common defense policy, which could lead to a common defense, if the Council so decides. Twenty years later, it still hasn't, the EU has only managed to reduce its level of ambition to 5,000 soldiers. At the end of the year, the European Council adopted the European security strategy, “A secure Europe in a better world”, the 2010 headline target and the concept of using the 1500 [9]Battle Groups (EUBG), which have never been implemented, whereas since[10]2007 one or two EUBGs have been operational.

In 2004, the European Defense Agency (EDA) was created, it has remained embryonic.

In December 2008, while Russia had attacked Georgia militarily in September, the European Council failed to update the 2003 “strategy”, but adopted a “Report on the Implementation of the European Security Strategy – Providing Security in a Changing World".

On December 1, 2009, after a few twists and turns, the Treaty of Lisbon entered into force. It renames the ESDP “Common Security and Defense Policy” (CSDP) and offers it some legal tools, such as Permanent Structured Cooperation, which the European Council will use, and minimalistically, only at the end of 2017. It reinforces the role of the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs (HR) and the CFSP, assisted by the European External Action Service (EEAS), made up of staff from the General Secretariat of the European Council, the European Commission and national diplomatic services. It makes the HR a Vice-President of the European Commission, who chairs the Foreign Affairs Council and the Management Board of the European Defense Agency. A largely incomprehensible text, the Treaty of Lisbon has disappointed the hopes it had raised, in particular by the creation of the HR function and the EEAS. This was predictable, since a treaty could not create unity of politico-military command. Only a federal constitution could.

In 2016, following the British vote on Brexit, the European institutions will multiply initiatives in favor of a poorly designed “European defence”. These multiple declarations of intent and the beginnings of implementation do not fill our capability gaps, because the political will is not sufficiently sustainable to achieve significant and lasting progress. On 15 December, the European Council approved a comprehensive EU strategy that was somewhat more comprehensive than that of 2003: it included the list of threats, but it did not set priorities or define the military capabilities capable of countering them. EU leaders are unable to sketch intergovernmentally the contours of a European army, to collectively answer the question of whether or not Europe needs nuclear deterrence, heavy bombers, aircraft carriers, attack submarines, armored divisions, special forces, etc., or only troops capable of peacekeeping and humanitarian action. This is because the perception of threats is not the same for all Europeans. From Lisbon, Russian tanks are invisible. For the inhabitants of Tallinn, Daesh and Al-Qaeda are concepts alien to everyday life.

On 7 May 2017, Mr Macron was elected President of the Republic. On 18 May, defense ministers agreed on the Coordinated Annual Defense Review (CARD), linked to the [11]EU Capacity Development Plan (CDP) and the NATO Defense Planning Process (NDPP). The Commission announces the creation of a European Defense Fund (EDF).

In 2018, through Regulation (EU) 2018/1092, the EU established the European defense industrial development program (EDIDP), which aims to support the competitiveness and innovation capacity of the Union's defense industry. TheHR, Ms Mogherini, proposes replacing the Athena mechanism with a “European Peace Facility”. It now finances the common costs of EU military operations and missions and strengthens partner states, mainly Ukraine, whereas it was designed for the Sahel. Neglected by Europe, the states of the region have turned to Russia.

The EU has not reduced tensions between Russia and Georgia or Ukraine, between Israel and Palestine, between the US and Iran, or in Libya, Syria, the Sahel, the Horn of Africa, Central Africa, Venezuela or Colombia. The EU's insignificance on the international stage and the impotence of European diplomacy are obvious.

How can we hope for a better future for Europe after the Covid-19 pandemic, the desire expressed by Mr. Xi to quickly annex Taiwan, the ambiguous attitude of Mr. Erdoğan and the wars that Putin is waging: high intensity to Ukraine, low intensity to Georgia and Moldova, hybrid to the West, they disrupt geopolitical balances and slow down economic growth. It has become very difficult to predict the likely evolution of Europe and the world, even in the short term. European leaders should give priority to the return of peace to Eastern Europe and the Sahel, because without it nothing is possible. This requires a more united Europe to be more powerful.

Unfortunately, the opposite is true. As a result of their division and their military and geopolitical insignificance, it was without any of the European leaders that in January 2022, Russians and Americans were discussing security in Europe.

Since February 24, 2022, the war in Ukraine has finally made the European peoples and their leaders aware of the extreme weakness of our armies, including those of the France and the United Kingdom. It has shown that our governments, our general staff and our defense industrial base are not able to quickly fill our capability gaps, due to a lack of political-military unity of command. Our leaders could federate our states, but so far none wants to. That is why European defense does not exist. That is why the military aid provided by the Europeans to Ukraine is real, but inferior to what is needed and that provided by the Americans and the British.

The only response that the European Commission and Council have found as tensions have risen is to submit more and more to the United States of America, because Mr Biden is much less brutal and more skilful than his predecessor. Parliamentarians have passed laws to reduce the price of medicines, they are fighting for the maintenance of the right to abortion. His administration has reduced the tuition debts of many higher education graduates, revived the economy, and invested significant sums in the fight against poverty and the energy transition. Mr. Biden has masterfully led the Western coalition since the beginning of the high-intensity war in Ukraine. The fact is that he will be 82 years old at the end of 2024 and he is not very charismatic, but voters in 2024 should vote more according to their interest rather than their beliefs.

In this context, the voluminous (116 pages) proposal of 17 August to amend the EU Treaty that Mr Verhofstadt (Renew Europe), Mr Simon (European People's Party), Mr Freund (Greens/European Free Alliance) and Mr Saryusz-Wolski ( European Conservatives and Reformists), as well as Mrs Bischoff (Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats), seem to want to carry, seems singularly unrealistic. It would tend to change the way the EU operates, and the name of its institutions. It would impose qualified majority voting and ordinary legislative procedures in dozens of areas, including defense, taxation and foreign policy. The European Commission would be renamed “the EU executive”. Parliament's powers would be greatly expanded. The EU would have exclusive competence on all environmental and climate issues, and shared competence with member states on almost all other matters. Although the authors of the proposal are not wrong to say that the enlargement of the EU to include the Western Balkans, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine would require profound changes in the functioning of the EU, even if Germany insists on the need to change qualified majority voting and increasing the EU budget to make enlargement possible, the memory of the failure of 2005 dissuades most governments from trying to have their voters change the EU Treaty.[12]

Rather than proposing a treaty change that has no chance of succeeding, these Members of the European Parliament would have done better to embark on the path leading, not 27 states, towards a constituent assembly, but only an expandable core of states, as was done for the Schengen and euro areas.

[1] See Alfred Caen, “The Western European Union and NATO. Building a European Defense Identity within the Context of Atlantic Solidarity”, Brassey's, Atlantic Commentary No. 2, London, 1989.

[2] See Alfred Caen, “A new role for WEU?” in Europe in formation, 1986, p. 53-66, http://www.ena.lu/ 13 / 02 / 2011.

[3] The CFSP does not constitute the totality of the EU's external relations policy, which includes trade, development or humanitarian policy, but also the external aspects of internal community policies (agriculture, environment, transport) as well as judicial and police cooperation in criminal matters. All these components of the EU's external policy have their own way of operating.

[4] See Henri Bentegeat, “What aspirations for European defence? » In Álvaro from Vasconcelos (dir.), What European defense in 2020?, Paris, IESUE, 3e ed., March 2010, p. 105.

[5] Any decision requires the consent of Catholic Croats, Orthodox Serbs and Muslim Bosniaks. lake Caroline de Gruyter, “Morrelen aan de foundations van de Europese Unie” in From Standard, https://www.standaard.be/cnt/dmf20220113_98107654, 14/1/2022.

[6] See Henry Kissinger, The New American Power, New York, 2001, trans.. Odile Demange, Paris, Arthème Fayard, 2003, p. 60.

[7] See Sven Bishop, Jo Coelmont, Europe Strategy and Armed Forces, The Making of a distinctive power, London and New York, Routledge, 2012, pp. 57-60; Fabien Terpan, The foreign, security and defense policy of the European Union, Paris, La documentation française, 2010, p. 55-60.

[8] The IESEU, headquartered in Paris, provides the HR with analysis and some forecast, contributes to the development of the CFSP by analyzes and recommendations and enriches the strategic debate in Europe within its network of experts of policy-makers. Lake Europe, The European Union Institute for Security Studies, , 16/10/2011.

[9] European Council A secure Europe in a better world, European Security Strategy, adopted on 3/12/2003, http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cmsUpload/031208ESSIIFR.pdf, 13/6/2011.

[10] Thes GT1500 or EU battle groups Count 1,500 men, deployable in less than 10 days for a period of up to 120 days.

[11] To see [Link no longer available] https://eda.europa.eu/what-we-do/EU-defence-initiatives/coordinated-annual-review-on-defence-(card). In 2020, it was clear that the CARD and the CDP are not at the level of the NDPP.

[12] Nicholas Vinocur, “MEPs pitch treaty change in radical (but unlikely) EU overhaul” in Brussels Playbook from Politico, 1/9/2023.